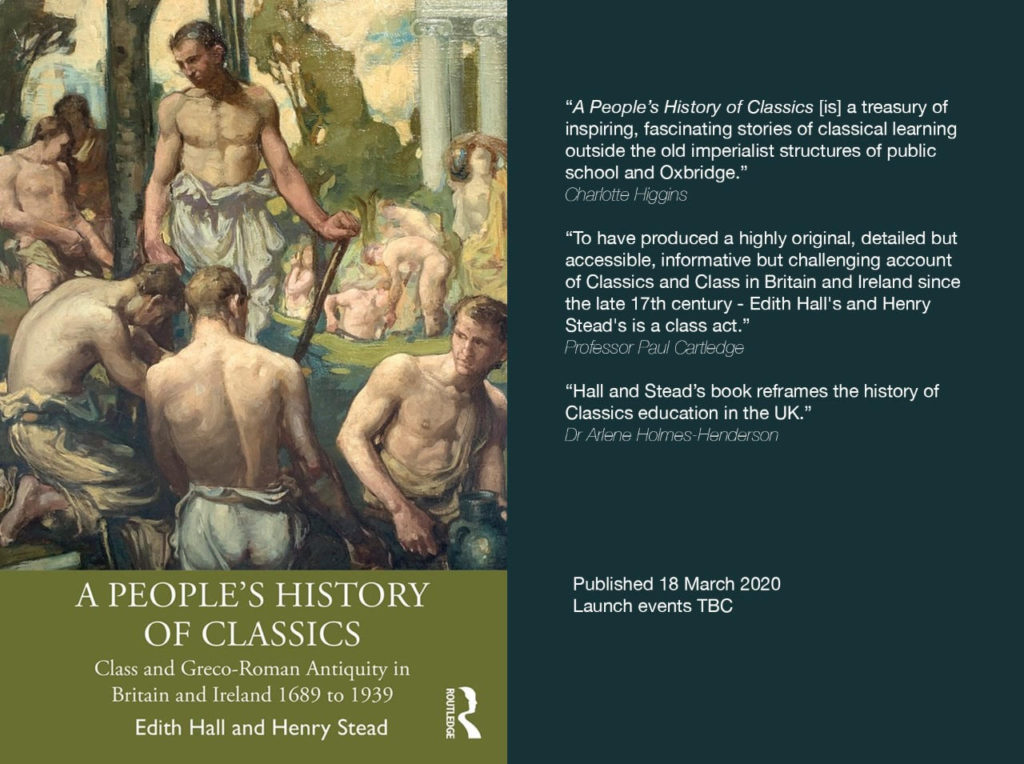

A People’s History of Classics began life as an AHRC-funded research project based at King’s College, London called Classics and Class in Britain 1789-1917. Our primary aim was to present and amplify the many lost voices of British working-class men and women who engaged with ancient Greek and Roman culture throughout the period. We wanted to show the richness and diversity of the responses to ancient Greece and Rome among those who are often thought to have been excluded from it. By presenting their stories now, via the Archive of Encounters, we hope that their example may inspire a more inclusive atmosphere for participation in classical culture across society today.

Our modern-day perception of the historical relationship between Classics and the divisions between citizens on the criterion of social class has long been distorted because the crucial voices — those of the working class — have not been heard. An exploratory conference organised by Edith Hall which was funded and hosted by the British Academy in July 2010 revealed that this ‘exclusionist’ model is usually taken for granted, and conventionally supported by a few passages in canonical 19th-century authors such as Dickens, Eliot, and Hardy. The meeting also underlined the neglect suffered by the evidence for contact with Classics produced by working-class people themselves (autobiographies, memoirs, letters, records of recreational activities, political banners, leaflets). Some of the essays from this conference may now be read in our book Ancient Greek and Roman Classics and the British Struggle for Social Reform (Bloomsbury, 2015).

The period under examination was that when class identity and conflict in Britain were at their most acute and self-conscious. The chronological scope was determined at the earlier end by the emergence of social ‘class’ as a category used in the modern sense after the French Revolution. The term ‘Classics’ has, since the early 18th century, been used in English to designate the ancient Greek and Roman authors, languages, and civilisations, and the institutional study of them. The term ‘class’ in the social sense begins in around 1770 with the industrial revolution and its decisive reorganization of society, when in it began to replace the feudal terminology of ‘rank’ and ‘order’. The online archive did not limit itself to the project’s geographical or chronological scope. We wanted to explore and learn from every class-conscious classical encounter we came across.

How did working- and lower-middle-class people access information about the ancient world? And how did they feel about it? How much Latin and Greek language, if any, had they learned? How were responses to individual ancient texts, authors and artefacts affected by the political agenda of the reader or viewer? Which ancient texts have proved most susceptible to class-conscious readings? What is the relationship between class and canon? Did Non-Conformists and Christian Socialists invoke classical authorities, or did they disapprove of the ‘corrupting’ study of pagan antiquity? Does gender interfere with the reading of the working-class subject? Is there is a relationship between specific working occupations and the acquisition of education?

In the third millennium, more than two decades after the fall of the Berlin wall, social class has moved back up to the top of the social agenda. Our research is intended to contribute to a shift in public perceptions about the class connotations of ancient Greek and Roman antiquity, emphasising its status as an inherited cultural property to which everyone has right of access.

Professor of Classics at King’s College, London, Edith Hall was the Principal Investigator of ‘Classics and Class’. Since being awarded the Hellenic Foundation Prize for her Oxford doctorate (1988), Edith has held posts at Cambridge, Oxford, Durham and London Universities. She has published twenty books. She is Co-Founder and Consultant Director of the Archive of Performances of Greek & Roman Drama at Oxford and Chairman of the Gilbert Murray Trust. She has won funding for research from the AHRB, the AHRC, the Leverhulme Trust, the British Academy, the Centre for Hellenic Studies in Washington, and has recently been awarded a Humboldt Research Prize and the Erasmus Medal of the European Academy. She appears regularly on BBC Radio, and has acted as consultant to professional productions of ancient drama at the Royal Shakespeare Company, the National Theatre, Northern Broadsides, Theaterkombinat and other professional companies. Her personal website contains further information: www.edithhall.co.uk.

Henry Stead is Senior Lecturer in Latin at the University of St Andrews. He worked as the Post-doctoral Research Associate on C&C. He is author of A Cockney Catullus (OUP, 2015), a study of the reception of Catullus in Romantic Britain. His research interests include: Leftist cultural history, the reception of classical culture in Britain and the former Soviet Union, translation of ancient literature, cross-media poetry, and Roman poetry. He translates ancient poetry and plays, including: ‘Moretum’ (from the “Appendix Virgiliana”), ‘Attis’ (Catullus 63 | 2014), ‘Seneca’s Medea’ (Stephen Spender Prize, 2011), and ‘Prometheus Chained’ (Sheffest, 2012). He was director of the cross-media poetry platform London Poetry Systems, and held a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship (2016-2019) which resulted in the ongoing research project Brave New Classics, a study of the relationship between classical culture and communism in Britain from the Russian Revolution to 1956.

AFFILIATED PROJECTS