Description

Sing along to the lays of Mary Collier, the Washerwoman Poet of Petersfield, who trumped the Thresher Poet, Stephen Duck’s classical references in her The Woman’s Labour. Much about her autobiographical note has the distinct whiff of fiction, but as ‘she herself says’: when writing her book she was an invalided and poverty-striken elderly woman confined to a garret in Alton. As readers we are encouraged to imagine her finally–after a life spent scrubbing linen–taking to writing down those poems, which had survived for so many decades in her memory and songs.

Sing along to the lays of Mary Collier, the Washerwoman Poet of Petersfield, who trumped the Thresher Poet, Stephen Duck’s classical references in her The Woman’s Labour. Much about her autobiographical note has the distinct whiff of fiction, but as ‘she herself says’: when writing her book she was an invalided and poverty-striken elderly woman confined to a garret in Alton. As readers we are encouraged to imagine her finally–after a life spent scrubbing linen–taking to writing down those poems, which had survived for so many decades in her memory and songs.

Casting her mind back to when she lived and worked in Petersfield, washing and brewing, she recalls: ‘Duck’s Poems came abroad, which I soon got by heart; fancying he had been too severe on the female sex, in his Thrasher’s Labour, brought me to a strong propensity to call an Army of Amazons to vindicate the injured sex: therefore I answered him to please my own humour, little thinking to make it public; it lay by me for several years, and by now and then repeating a few lines to amuse myself, and entertain my company, it got air.’

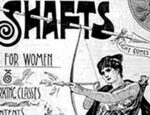

Her desire to invoke an ‘Army of Amazons’ betrays a cultural knowledge beyond that commonly associated with one of her class, especially one who had received scarcely a year of formal education. Had this been a one-off reference to classical culture, we might think it a common expression diffused into common speech. The amazons would, after all, become mythological representatives of campaigners for universal suffrage in the 19th century (see here). But it does not stand alone. In her poem The Woman’s Labour, a response in verse to Duck’s misogynistic poem, she picks up on (and perhaps mocks) his lofty classical references. She trounces his suggestion that men work harder at harvest time than the women by stating plainly that the women—after a long day’s work in the field laying out and turning the hay—have then to go home, get the house in order, prepare dinner, mend the children’s clothes, etc. While the man’s labour, she implies, begins and ends in the field.

Her first classical allusion in the poem is to the myth of Jupiter and Danae, an extremely popular subject for visual artists in the modern world and antiquity (e.g. Gustav Kilmt’s Danaë – top):

JOVE once descending from the clouds, did drop

In showers of gold on lovely Danae’s lap;

The sweet tongu’d poets, in those gen’rous days,

Unto our Shrine still offer’d up their lays:

But now, alas! that golden age is past,

We are the objects of your scorn at last.

In the olden days, the gods were attracted to mortal women, poets took them as their muses. Now, she argues, those days have passed.

And you, great DUCK, upon whose happy brow,

The muses seem to fix their garland now,

In your late Poem boldly did declare,

Alcides’ labours can’t with yours compare.

Hercules’ labours now, and a classicizing reference to the poet wearing a wreath woven by the muses. These are commonplaces of English poetry, but still I’m not convinced of the authenticity of this poem. The use of ‘Alcides’ rather than Hercules (as Duck uses) shows an extra level of classical knowledge. It names Hercules by his father’s name (literally ‘son of Alcaeus’), which was extremely common in classical poetry, but far from common in English parlance. Ought we perhaps to doubt the authenticity of Collier’s poem? Her book carries the names of nine Petersfield residents, all attesting to her authenticity, which to a cynic proves only that the booksellers knew that the text appeared spurious. Whoever wrote this poem (let’s call her [or him] ‘Mary’), has attempted–and succeeded–to out-Duck Duck with his decorous and whimsical classical references – for an example see here. In the end of the poem Mary writes:

BUT to rehearse all labour is in vain,

Of which we very justly might complain:

For us [women], you see, but little rest is found;

Our toil increases as the year runs round.

While you to Sisyphus yourself compare,

With Danaus’ daughters we may claim a share;

For while he labours hard against the hill,

Bottomless tubs of water they must fill.

In Duck’s Thresher’s Labour he does indeed refer to himself as Sisyphus, and by alluding to another less obvious and female myth of perpetual labour, that of the Danaides, Mary Collier yet again trumps Duck.