Description

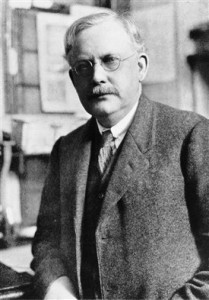

Meet Albert Mansbridge (1876-1952) the largely self-educated son of a carpenter who would live to pioneer adult education in Britain–co-founding the Workers Educational Association (WEA)–and champion the provision of Classics in all educational establishments.

Meet Albert Mansbridge (1876-1952) the largely self-educated son of a carpenter who would live to pioneer adult education in Britain–co-founding the Workers Educational Association (WEA)–and champion the provision of Classics in all educational establishments.

In 1923 he wrote to the American journal Classical Weekly an open letter, which was duly printed by its editor, the New York classical scholar Charles Knapp (1868-1936):

“… it has been continually thrust upon me as the result of practical work united with observations that those who succeed best in awakening an interest among them [working men and women] or in satisfying the interest when it is awakened, are men and women who have taken the Classical Schools at either of our great universities. …

This being so, it naturally follows that, since high ability is confined to no one class or experience, the children of working men and women who have the ability and desire should have the opportunity to pursue classical learning. This implies that there should be scattered through the community a number of teachers who are able, not merely to impart the beginnings of Latin and Greek, but who are able to perceive and to estimate properly the minds and capacities of their students.

In every community there must be a sufficient proportion of individuals who are able to adopt a larger view of life, and the best instrument for the development of this in our time has undoubtedly been classical education. If a people is given over to organising its education on vocational and occupational lines, it will, in the long run, fail to reap the highest advantages.

Thus it is clear that the Universities and Colleges of the country should on no account fail to develop and sustain an efficient classical department or school.

In conclusion I may say that in addition to my experience among working men and women I have sat upon several Governmental Educational Commissions, including that which reported some three years since on the Teaching of Modern Languages. The testimony of the witnesses before the Commission appeared to be unanimous that, whether for the purpose of high business or for the actual study and teaching of modern languages, that man was best who had had a preliminary classical training.”

What the specific trigger was for Mansbridge to write this letter remains something of a mystery. There was, however, extremely heated discussion in the 1920s about adult education. The classical education appeared to many as a relic of the old world order, and not only to the radical left. In the words of fellow educationalist William Henry Hadow there was: “[a] widespread feeling that the classical culture by itself no longer afforded an adequate preparation for modern life”. The Sciences, Economics, Politics and Modern Languages were deemed to be of at least equal importance to Classics. Such debates had been raging in Britain throughout the 19th century, but educational reform was remarkably slow.

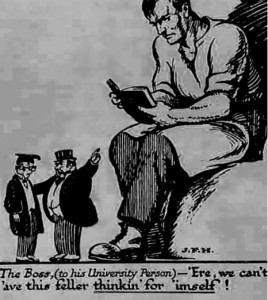

It was for the kinds of ostensibly conservative educational beliefs that Mansbridge displays in this letter that most riled his critics, who saw the (now state-funded) WEA as an extension of the existing instrument of capitalism, ie. conventional higher education. After World War One many workers returned home to no jobs with a keen desire to educate themselves. Plebs League and Central Labour College courses were consequently oversubscribed. In 1921, to meet such demand, the National Council of Labour Colleges (NCLC) was formed, subsuming the Plebs League. With its independent and radical ethos, it stood in ideological opposition to the WEA. The two different (though both unquestionably progressive) approaches to adult education served to intensify debate about what a workers’ curriculum should contain.

Whether or not the study of the Greek and Roman classics were relevant in the new world continued to be hotly contested through the crisis-ridden 1930s, when many of the newly politicised, classically-educated elite–sympathetic to the workers’ struggle for social reform–questioned the efficacy and cultural supremacy of the educational products from which they were born to profit.