Description

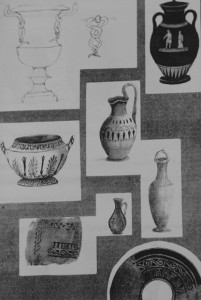

Meet Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn, the Swansea industrialist responsible for a famous line of inexpensive ceramics imitating ancient Greek models, produced in his factory, the Cambrian Pottery, in the mid-19th century. At the time he employed no fewer than 162 workers, including at least sixteen women; they must all have become familiar with the ancient designs of the vases and plates which they produced. The name of the line–“Etruscan ceramics”–was a misnomer: the artefacts’ shapes and illustrations were mostly copied from classical Athenian and South Italian vases. Using moulds, the potters and painters produced pottery in most of the canonical Greek shapes—the aryballos, oinochoe, kylix, pyxis, pelike etc. They decorated them with figures from Greek mythology including Odysseus, Amazons, Poseidon, Eros, Hector, Zeus, Hera, and Helios driving his horses. Dillwyn had joined the management of his father’s company in 1831.

Meet Lewis Llewelyn Dillwyn, the Swansea industrialist responsible for a famous line of inexpensive ceramics imitating ancient Greek models, produced in his factory, the Cambrian Pottery, in the mid-19th century. At the time he employed no fewer than 162 workers, including at least sixteen women; they must all have become familiar with the ancient designs of the vases and plates which they produced. The name of the line–“Etruscan ceramics”–was a misnomer: the artefacts’ shapes and illustrations were mostly copied from classical Athenian and South Italian vases. Using moulds, the potters and painters produced pottery in most of the canonical Greek shapes—the aryballos, oinochoe, kylix, pyxis, pelike etc. They decorated them with figures from Greek mythology including Odysseus, Amazons, Poseidon, Eros, Hector, Zeus, Hera, and Helios driving his horses. Dillwyn had joined the management of his father’s company in 1831.

His wife Bessie created the designs after studying vases in the British Museum. Their ambition was to fuse ancient designs with the local clay of the family estate at Penllergaer near Swansea, which, when fired, produced a fine red colour similar to the terracotta hue of in ancient black- and red-figure vases. The pots were not only made by members of the local working class, but also aimed at a much less wealthy class of consumer than, for example, Wedgwood pottery: Dillwyn ware was far cheaper to produce, because it was moulded rather than thrown on a wheel. An advertisement in Art Journal claimed the pots “promise much towards carrying into the more humble homesteads of England forms of beauty in combination with useful ends, and in placing in the hands of all, ornaments of a high character at a cheap rate.” In fact, they cost between 2 shillings and 3 shillings and sixpence—just about affordable as a luxury even by the local miners, who earned around £50 annually. The brand soon failed. Perhaps no miner could see the point. People who could afford porcelain assumed that cases made from “flower-pot” clay would be coarse and rustic; others were suspicious of merchandise which looked so refined yet was available at such an affordable price. But Dillwyn ware continued and continues to be viewed in museums from Swansea to Bethnal Green.

His wife Bessie created the designs after studying vases in the British Museum. Their ambition was to fuse ancient designs with the local clay of the family estate at Penllergaer near Swansea, which, when fired, produced a fine red colour similar to the terracotta hue of in ancient black- and red-figure vases. The pots were not only made by members of the local working class, but also aimed at a much less wealthy class of consumer than, for example, Wedgwood pottery: Dillwyn ware was far cheaper to produce, because it was moulded rather than thrown on a wheel. An advertisement in Art Journal claimed the pots “promise much towards carrying into the more humble homesteads of England forms of beauty in combination with useful ends, and in placing in the hands of all, ornaments of a high character at a cheap rate.” In fact, they cost between 2 shillings and 3 shillings and sixpence—just about affordable as a luxury even by the local miners, who earned around £50 annually. The brand soon failed. Perhaps no miner could see the point. People who could afford porcelain assumed that cases made from “flower-pot” clay would be coarse and rustic; others were suspicious of merchandise which looked so refined yet was available at such an affordable price. But Dillwyn ware continued and continues to be viewed in museums from Swansea to Bethnal Green.

n.b. around 1840