Description

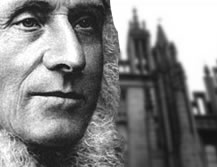

Meet Alexander Bain, son of a Scottish hand-loom weaver and a weaver himself, who – after a basic education at dame school – struggled to educate himself around his job. After years of evening classes and private tuition, he managed to win himself a place at Aberdeen’s Marischal College—and eventually became one of Scotland’s foremost philosophers, appointed Regius Chair of Logic at the newly created University of Aberdeen in 1860.

It was at Gilcomston Church School between 1826-9 where Bain began his classical education: “I was put through the Rudiments, and found the memory work not at all congenial—but still I did it; and, in the conjugations of the verbs, I soon hit on the device of shortening the labour by marking agreements and differences. Before leaving the school, I had the rudiments pretty well by heart, and had begun to translate short sentences for an easy collection.” After school he first earned his crust through being an errand-boy to an auctioneer, soon reverting to his father’s profession of weaver. During this time, he enrolled in evening classes and embarked on his astonishing self-education. He managed to be admitted for free to the Grammar School in Aberdeen for three months, in which time (he tells us) he consolidated his Latin and learned ancient Greek. Although he was disappointed not to win a bursary for Marischal College—competing against classmates who had been consistently in grammar-school education for years—he did manage to gain a £10 bursary (through the equivalent of clearing).

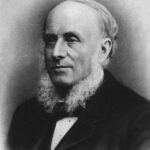

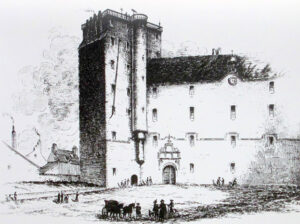

At Marischal (pictured left – as it was before 1835) he was taught more Greek language, ancient history and some Greek literature—including Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrranus, Herodotus’ Histories, Andreas Dalzel’s Collectanea Graeca Majora, and Thucydides. He continued his Latin, translation and composition, and read Virgil’s Aeneid book 6, poems by Horace and the Livy’s Roman History. All the while he was at college, he supplemented his bursary by teaching Mathematics at the Mechanics’ Institute. He left for London in the 1840s, where he became friends with the Scottish philosopher and economist, John Stuart Mill, and the political radical and classical historian, George Grote. In the 1850s Bain would lecture in Geography and Psychology at Bedford College for Women.

At Marischal (pictured left – as it was before 1835) he was taught more Greek language, ancient history and some Greek literature—including Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrranus, Herodotus’ Histories, Andreas Dalzel’s Collectanea Graeca Majora, and Thucydides. He continued his Latin, translation and composition, and read Virgil’s Aeneid book 6, poems by Horace and the Livy’s Roman History. All the while he was at college, he supplemented his bursary by teaching Mathematics at the Mechanics’ Institute. He left for London in the 1840s, where he became friends with the Scottish philosopher and economist, John Stuart Mill, and the political radical and classical historian, George Grote. In the 1850s Bain would lecture in Geography and Psychology at Bedford College for Women.

He read widely in religious and philosophical treatises, and was as familiar with ancient philosophy as he was with modern. In 1872 he took it upon himself—following the death of his friend, George Grote—to finish and prepare for publication (with Croon Robertson) Grote’s unfinished work on the Greek philosopher Aristotle. A few years earlier he also published in Macmillan’s Magazine a response to Grote’s Plato and the Other Companions of Sokrates.

Bain did not only write on philosophical matters, but was also a highly respected educationalist, twice wading into debates on the efficacy of the classical education, to which he referred as the ‘interminable Classical question’. Does learning Latin and Greek really prepare our youth for modern life? The question was hotly debated in 1879, as it had been a hundred years earlier by Tom Paine and others, and would continue to be for another hundred years, before finally fading away in the 1950s. Bain argued (successfully, he tells us) that the benefits in mental ‘discipline’ from learning Greek and Latin, could be acquired just as well by learning just one of the two ancient languages.

n.b. around 1830