Description

Misunderstand Aristophanes’ Frogs by reading it in the edition of Thomas Mitchell (1839), which offers an indictment of Athenian democracy. The edition, with its notes in English, became a chief conduit through which Victorian men had access to that play at school and university.

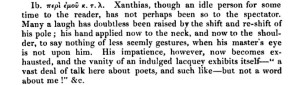

The detailed comments Mitchell made on the play are all from a patrician perspective which looks down on Xanthias, the clever, witty slave of Dionysus. When Xanthias speaks up during the dialogue between Heracles and Dionysus (Frogs 82-3), ‘the vanity of an indulged lacquey [sic] exhibits itself’. The same superior censure of the serving class emerges in Mitchell’s remarks on the dialogue between Xanthias and the underworld slave. In particular, Mitchell takes exception to Xanthias’ remark that masters can afford to be magnanimous, if all they do is pinein and binein (drink and fornicate, Frogs 701-3); he proposes that the whole dialogue must itself be accompanied by the drinking of the slaves, on the dubious ground that the sort of remarks they make are rarely made except under the influence of alcohol: ‘And do our two lacqueys hold a dry colloquy? Forbid it every feast of Bacchus, of which we ever heard! forbid it all the bonds which have tied lacqueyism together, since the world of man and master began?’

The detailed comments Mitchell made on the play are all from a patrician perspective which looks down on Xanthias, the clever, witty slave of Dionysus. When Xanthias speaks up during the dialogue between Heracles and Dionysus (Frogs 82-3), ‘the vanity of an indulged lacquey [sic] exhibits itself’. The same superior censure of the serving class emerges in Mitchell’s remarks on the dialogue between Xanthias and the underworld slave. In particular, Mitchell takes exception to Xanthias’ remark that masters can afford to be magnanimous, if all they do is pinein and binein (drink and fornicate, Frogs 701-3); he proposes that the whole dialogue must itself be accompanied by the drinking of the slaves, on the dubious ground that the sort of remarks they make are rarely made except under the influence of alcohol: ‘And do our two lacqueys hold a dry colloquy? Forbid it every feast of Bacchus, of which we ever heard! forbid it all the bonds which have tied lacqueyism together, since the world of man and master began?’

Mitchell’s introduction stresses the problem presented to Athens by the demagogues, or popular leaders of the free lower classes in Athens. They are dismissed as ‘the real deformity daily developing itself’; in democratic Athens, ‘the last knave was welcome as the first’; it was the ‘innate vices of the Athenian constitution’ that enabled such a man to put himself in power. Mitchell openly attacks democracy as a political ideal and opinion; his volume, of course, was published just a few years after the great Reform Act of 1832, at a time when the Chartists’ appeal for universal male suffrage had attracted the support of a prominent sector of the middle class. Thucydides, Xenophon, Aristophanes and Plato, says Mitchell, offer ‘so complete a view of the effects of this form of government… in the two great questions of civil freedom and moral excellence, that it must be to sin with the eyes open, if any portion of the world allow men of small attainments, and not always the most upright principles, to precipitate it into such a form of government again’. Here Aristophanic commentary becomes a naked weapon in the war against advocates of universal suffrage.

Mitchell’s introduction stresses the problem presented to Athens by the demagogues, or popular leaders of the free lower classes in Athens. They are dismissed as ‘the real deformity daily developing itself’; in democratic Athens, ‘the last knave was welcome as the first’; it was the ‘innate vices of the Athenian constitution’ that enabled such a man to put himself in power. Mitchell openly attacks democracy as a political ideal and opinion; his volume, of course, was published just a few years after the great Reform Act of 1832, at a time when the Chartists’ appeal for universal male suffrage had attracted the support of a prominent sector of the middle class. Thucydides, Xenophon, Aristophanes and Plato, says Mitchell, offer ‘so complete a view of the effects of this form of government… in the two great questions of civil freedom and moral excellence, that it must be to sin with the eyes open, if any portion of the world allow men of small attainments, and not always the most upright principles, to precipitate it into such a form of government again’. Here Aristophanic commentary becomes a naked weapon in the war against advocates of universal suffrage.